Paul’s Sewing Machine Hobby

First: This page is basically a log of my acquisitions. With something like 70 machines to describe, it has gotten very long, and it’s sorted unhelpfully in the order I got them. Readers presumably have different interests, so I’ve created some index pages which show only subsets of the machines, all ordered by age. Those pages link back here for more information. There are index pages for:

- All the machines, ordered by age (plus a version better on phones)

- Just the machines I still own

- “New England style” machines

- New Home machines, and their forebears

- Willcox & Gibbs machines

- Wheeler & Wilson machines

- Singers

- German machines

- Hand crank machines

- Treadle machines

- Electric machines

So, that out of the way…

I have a small collection of interesting (to me!) sewing machines. I didn’t really intend to start collecting, but once I had a few, and told people about them, I was offered more. And eventually, as I learned more, I started buying one here or there. But I figure I’m just the caretaker of these things for a while.

Most all my machines can sew. The goal is that they all should. I try to use them all occasionally, or, in the case of the very old ones, at least once. I sew a bit, but not well, and not nearly enough to justify more than one machine in the house. But I enjoy the cleverness and quality that went into their invention and design. Early sewing machines live at an interesting intersection of history, aesthetics, precision engineering, and domesticity, all of which I find compelling. I think of them as kinetic sculpture, or at least kinetic industrial art.

The machines appear here in the order I got them, intermixed with various sewing machine adventures or experiments.

Statistics: As of December 2025 I have 39 complete sewing machines. In general, they can all sew, except for one or two that maybe haven’t been restored, or are missing critical parts. They’re between 72 and 165 years old. A third of them are over 150, and 90% are over 100. 60% are from the 19th century. 19 are treadled machines (9 share a multi-use treadle), 18 are hand cranks, and 2 are full-time electric. (Several of the treadled machines also have motors, which I don’t usually use.) The 11 treadles take a lot of floor space!

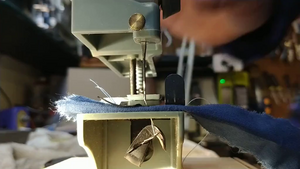

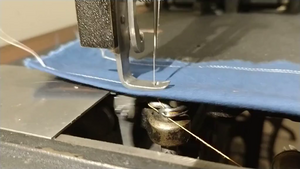

I also have a small collection of “stitching” videos, showing how various machines actually perform the act of sewing, on youtube. Some were filmed in slow motion, but I recommend slowing down playback for all of them.

Oh, and by way of thanks, and to give credit: the folks on the Victorian Sweatshop forum have been really friendly and helpful, as have the members of the TreadleOn mailing list. If you’re interested in old machines, those are the places to go! There are also a number of manufacturer-specific groups full of lots of good information at groups.io, and also, as much as I hate to admit it, on Facebook. (The trouble with FB is that searching for older information is almost impossible. It’s all focused on “now, now, now”.)

If you want to ask about anything here, or just make comments, drop me a line at pgf@foxharp.boston.ma.us . (But if you have questions about your own machines, you’re probably better off asking at one of the places I mentioned above. I’m not an expert, and only know my own machines well.)

The pictures are all clickable for larger versions. And if you want to skip the text, and just look at pictures, click on any picture and then use the arrows (or click on either half of the larger image itself) to navigate.

- Sewing machine background and trivia

- 1916 Singer 29-4 Leather Patcher

- c.1969 Singer Fashion Mate Model 237

- c.1900 Standard Rotary

- 1941 Singer Model 201-2

- 1916 Singer Model 66-1 Treadle

- c.1968 Singer Featherweight “White” Model 221K

- 1921 Willcox & Gibbs Automatic Silent Sewing Machine

- 1914 Willcox & Gibbs Automatic Silent Sewing Machine

- 1871 Singer “New Family”

- 1941 Singer Model 99K Hand Crank

- 1947 Singer Featherweight Model 221

- c.1880 Wheeler and Wilson No.8

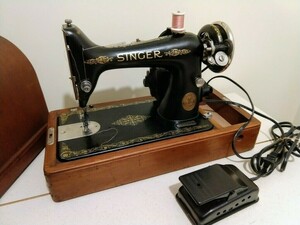

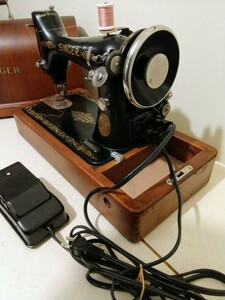

- 1922 Singer Model 99K-13, electric

- 1926-1950 Singer Model 20 Toy Chain Stitcher

- Willcox & Gibbs Hand Crank, with 1904 parts machine

- Custom Sewing Machine Display Bases

- 1871 Howe “Letter A”

- c.1918 Western Electric No.2 Portable

- 1937 Willcox & Gibbs Automatic Silent Sewing Machine, with electric cabinet

- 1906 New Home “New National”

- 1976 Sears Kenmore Free Arm Model 1946

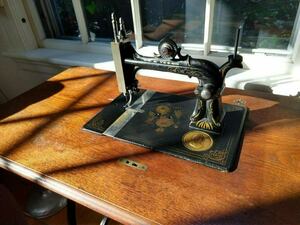

- c.1860 Charles Raymond (no.1)

- Willcox and Gibbs treadle base with 1893 parts machine

- Makeshift DIY spool winder

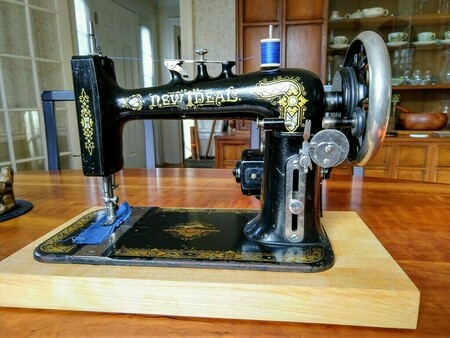

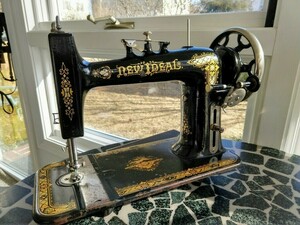

- 1906 New Home “New Ideal”

- 1931 Singer Model 101

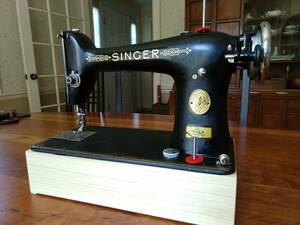

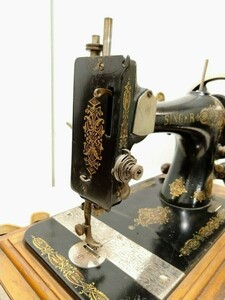

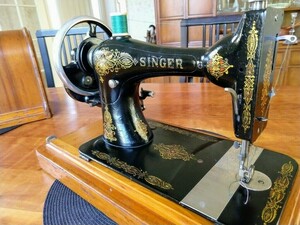

- 1906 Singer Model 15-30

- c.1873 Gold Medal “Home”

- 1888 Singer VS3

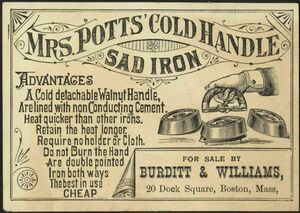

- Mrs. Potts’ Cold Handle Sad Iron

- Reattaching a loose bobbin end

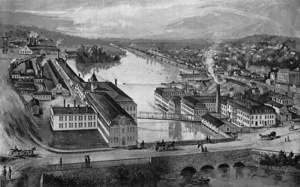

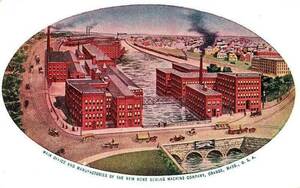

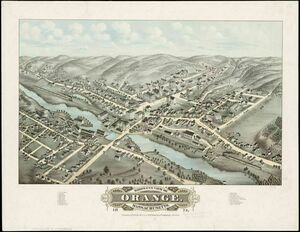

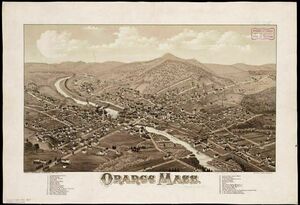

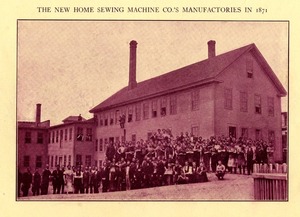

- A pilgrimage, of sorts, to Orange, MA

- 1921 Singer Model 15-30

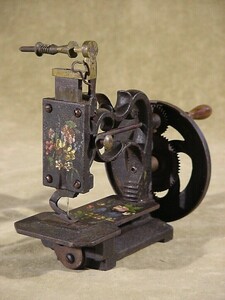

- 1920-1940 Müller Model 12C Toy Chain Stitch

- A visit to the Orange Historical Society

- 1877 Singer Model 12

- 1938 Singer Model 201-2

- c.1920 New Home “Midget”

- 1875 Willcox & Gibbs Automatic Silent Sewing Machine

- c.1861 Charles Raymond (no.2)

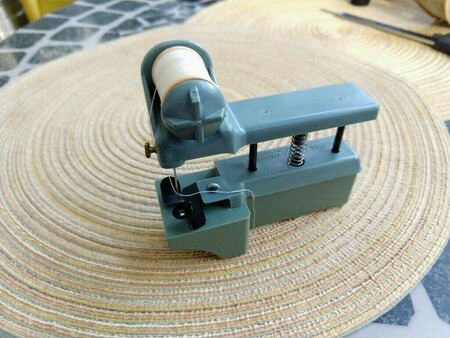

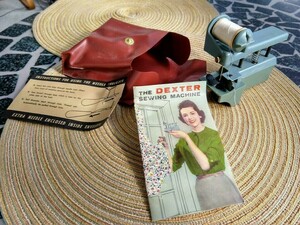

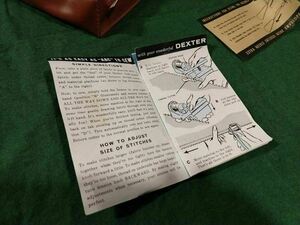

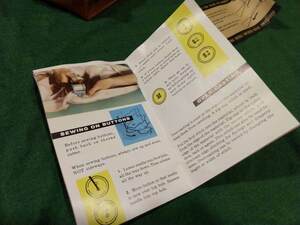

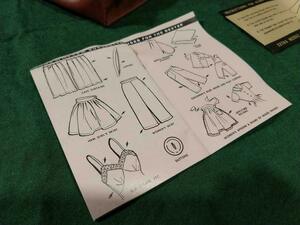

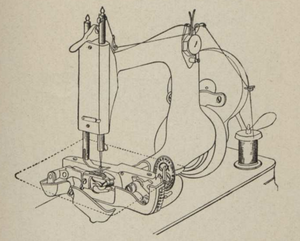

- c.1955 Dexter Sewing Machine

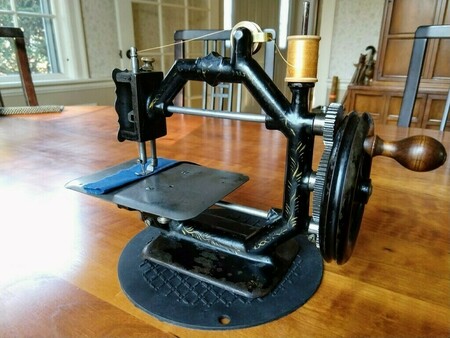

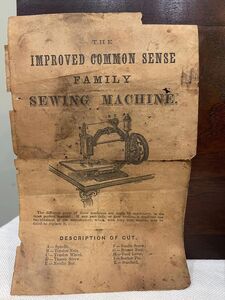

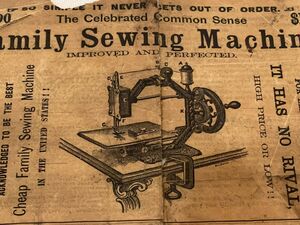

- c.1870 Gold Medal “Common Sense” Sewing Machine

- c.1900 Biesolt & Locke “Wettina”

- 1926-1950 Singer Model 20 Toy Chain Stitcher (no.2)

- c.1864 Willcox & Gibbs w/ glass tension

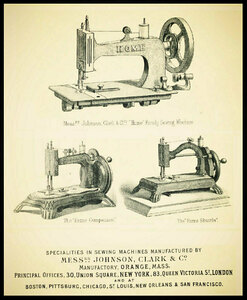

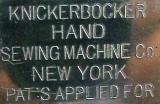

- c.1874 Johnson, Clark & Co. Home Shuttle

- 1887 Singer Automatic Chain Stitch Sewing Machine

- 1877 Davis Low Arm Vertical Feed

- 1878 White VS1

- Treadling a Featherweight

- 1947 Singer Model 201-2

- 1884 Singer “Improved Family”

- Gang of four

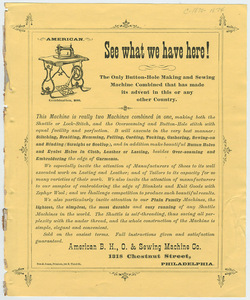

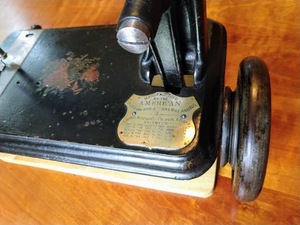

- c.1872 American Button-Hole, Overseaming & Sewing Machine Co. Model ‘M’

- c.1893 Atlas model ‘A’ / Bremer and Bruckmann “Brunonia”

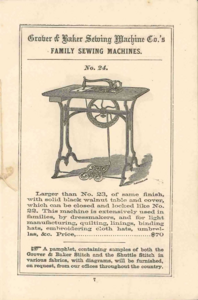

- 1866 Grover & Baker chain stitcher

- c.1889 Wheeler and Wilson No.9

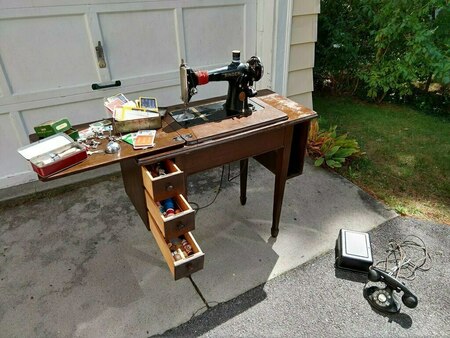

- It’s raining sewing machines!

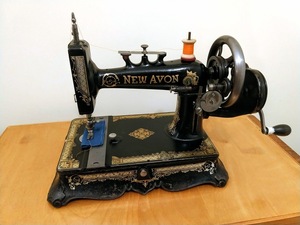

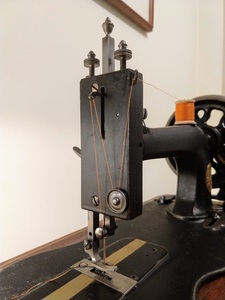

- 1918 New Home “New Avon”

- 1902 Frister & Rossmann

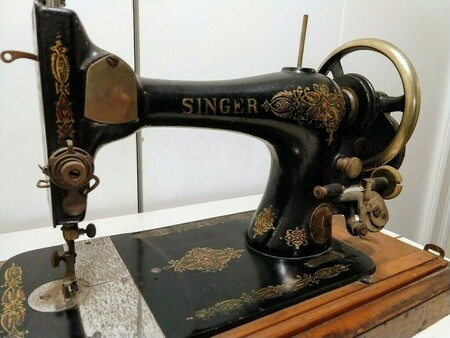

- 1886 Singer Model 12

- 1916 New White Peerless “Excelsior”

- c.1895 Hengstenberg “Robina”

- c.1919 Gritzner “R”

- 1925 Singer Model 99

- 1872 Wheeler & Wilson No.3

- One that got away

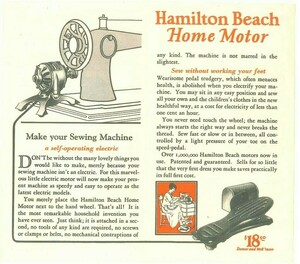

- Hamilton Beach “Home Motor”

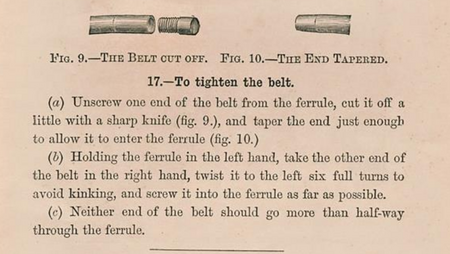

- Treadle belt ferrules

- Spool felts, and felt washers

- c.1871 American Button-Hole, Overseaming & Sewing Machine Co. w/ overseamer

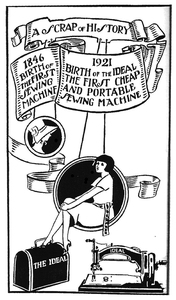

- c.1922 Salter’s Ideal Sewing Machine

- c.1892 Wheeler and Wilson No.9 parts machine and MUTT treadle

- 1920 Singer 127-3

- 1953 Necchi BU Nova

- c.1905 Jacoby “Eclipse” Fur Sewing Machine

- 1937 Singer Model 201-2

- c.1870 Little Wanzer

- c.1886 Jones Hand Machine

- c.1880 Royal St. John

- 1925 Singer Model 128

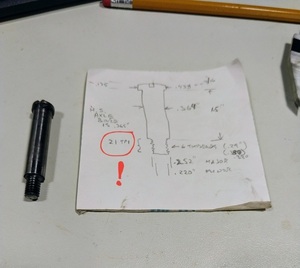

- Making new screws!

- c.1860 Charles Raymond (no.3)

- c.1870 Johnson, Clark & Co. Home Shuttle treadle

- Royal St. John with Mother-of-Pearl

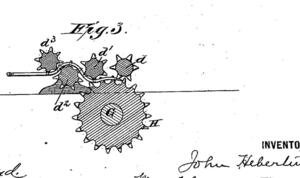

- c.1879 Heberling Running Stitch Machine

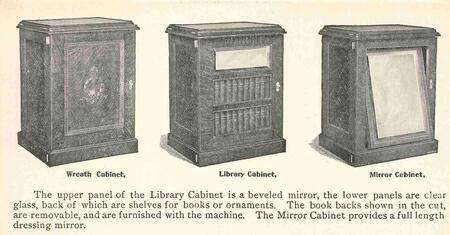

- Wheeler and Wilson Mirror Cabinet

- 1914 New Home hand crank with floral decals

- 1947 Singer 201K

Sewing machine background and trivia

-

For an absolutely top-notch intro to the history of the sewing machine, as well as first-class demos and simulations of how the machines work, you should watch this educational video. It’s very well done.

-

For a fascinating glimpse into Singer manufacturing, take a look at this factory video. It’s an amazingly complete overview of a major Singer factory: it’s got hand-poured molten iron, tumblers for 100s of sewing machine bodies at once, milling, stamping, polishing, dip painting, drop forging, needle straightening (by hand!), cabinet making, you name it. (It starts out a little slowly, with 7 minutes of long panning shots of the outside of the building, and of the stacks of raw materials. After that it picks up.)

-

At the turn of the 20th century, Singer was the largest furniture manufacturer in the world. This interesting article talks about that side of their business.

-

The Smithsonian has copies of Singer product catalogs from 1907 and 1908, which contain some amazing machines – like with 12 needles and bobbins, or with 6 foot wide beds. It lists my 29-4 as costing $40, or just $37 without the treadle base.

-

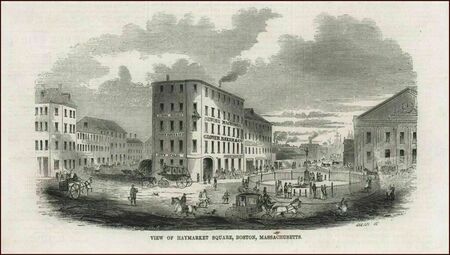

Also from the Smithsonian, this snippet from the introduction to some circa-1870 marketing materials for the Grover & Baker line of machines: “American genius has laid its latest achievement in the practical arts at the feet of Woman; this achievement is in turn by her everywhere being welcomed to its rightful domain. The Sewing Machine is already becoming the ‘angel of the house’ the world over.” Colorful, yes, but it’s also a good summation of the impact the household sewing machine had in the late 19th century.

-

The 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica (I happen to have the full set) has an article on the history and operation of the sewing machine. If you’re interested in vintage machines, it covers the major players nicely in just a couple of pages, with wonderful flowery and technically precise language. (The article is sandwiched between equally detailed articles on “Sewerage” and “Sex”. :-)

-

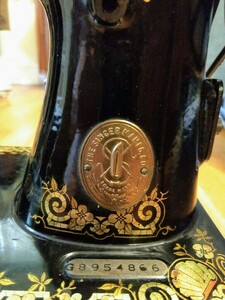

ISMACS has charts of Singer serial numbers on their website. I’ve converted those charts to text files, which I find easier to use. But as of 2023 or so, the easiest way to look up Singer (and Willcox & Gibbs) serial numbers is using this great web tool.

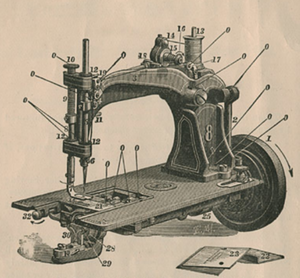

1916 Singer 29-4 Leather Patcher

| written January 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I purchased my Singer 29-4 (s/n G4763444) in June of 1998 from the owner of The Village Cobbler shoe repair shop in nearby Lexington, Massachusetts. It was a spare machine, stored at home in his cellar. These machines were built between 1896 and 1922. Mine is from roughly 1916.

It’s an interesting machine, and not only for its air of steampunk

authority. The arm containing the bobbin is designed to be slender

enough to fit into the toe of a boot. The feed mechanism isn’t

implemented with the usual feed dogs, which would rise from under the

presser foot to pull the material forward. Rather, the presser foot

lifts and “walks”, dragging the material underneath on its backward

stroke.

In addition, the presser foot can be rotated 360 degrees, to allow

sewing in any direction without turning the material or object being

sewn. The thread runs down through a hole in the center of the needle

bar, so it doesn’t get twisted up when the presser foot rotates.

The only significant repair I’ve made was to the bobbin “case”: a needle tip broke off when I ham-fistedly tried sewing something much too heavy, and the tip was dragged down beside the bobbin where it jammed and caused score marks in the cast iron hole surrounding the bobbin. This scoring snagged the thread as it passed under the bobbin, and the machine would no longer sew. The fix involved emery cloth, and JB Weld, and more emery cloth, in order to smooth out the walls of that hole.

Unlike most sewing machines, instead of just one set of drive

pulleys on the machine and treadle base, it has two. This gives it

two drive ratios, for different tasks. With my meager skills, it always

stays in “low gear”. :-)

Someday, I’d like to build a replica of the table accessory that

Singer used to make.

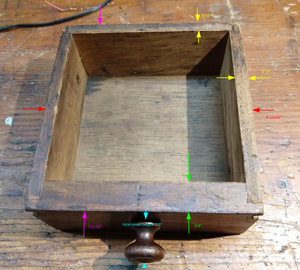

Someone asked me for the dimensions of my 29-4’s drawer, because they wanted to reproduce it. Those measurements are here.

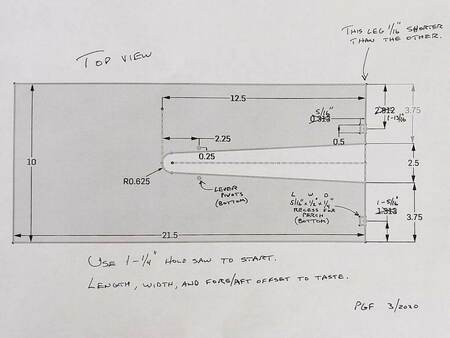

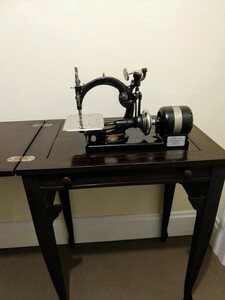

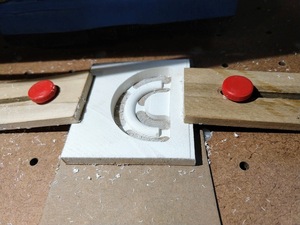

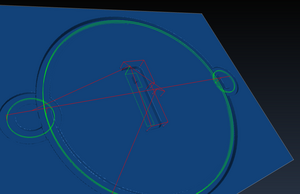

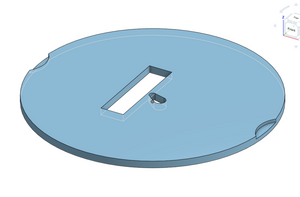

An extension table for the 29-4

| written March 2020, while hiding from the novel coronavirus | [index] |

| and updated again, May 2021, to add more details | [index] |

I decided I finally needed to do something about not having a sewing table for the 29-4. I use it often – camping equipment, repairs, heavy materials – and balancing the work on just the skinny snout is often a pain, and unnecessarily difficult. I got the machine in ‘98, and I’ve wanted a table ever since.

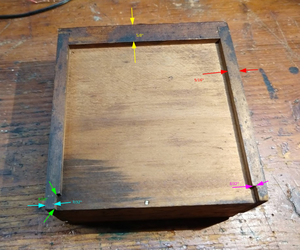

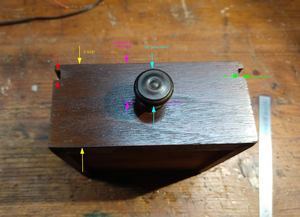

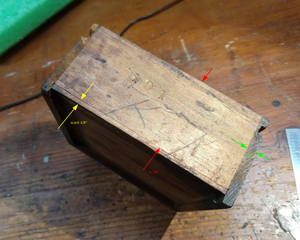

I was lucky that my urge to make the table coincided with having on hand some pieces of a rolling kitchen island cart that I’d salvaged from someone’s curbside trash. (Hey, solid panels are hard to come by! And I didn’t want to use plywood.) One of the cabinet doors that I’d saved was a dandy size for my table. You’ll notice some extra useless holes in my finished table – they’re inherited from the role as kitchen cart.

I started with measurements from a friend on the VSS forum, adjusted them, made some mistakes, readjusted, but in the end – it turned out well. I used a little furniture oil to finish it, but I’m so happy to have it that I don’t really care what it looks like!

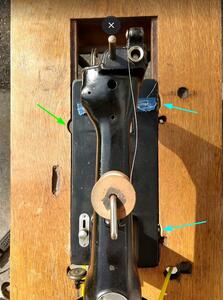

With the locks twisted in place, it’s completely solid, which is something I’d worried about when thinking about how to build it. From the parts lists I’ve seen, I think the Singer table had some sort of locking mechanism, but I’ve never seen a picture of the underside of an original table. I had to design the levers so as not to touch the rotating parts under the bobbin.

And about the end that hooks onto the perch points on the machine: I didn’t want to use anything that would wear or damage the paint on those points (at least not too much), so that ruled out steel or aluminum, which I think was what Singer used. I thought of using wood strips, but eventually realized a piece of stout leather would do the job. (I only had faux leather – don’t tell anyone.)

There’s also a higher resolution version here.

A couple of things that didn’t make it into the drawing: The leg and table are both 3/4” thick. The hinged leg is 11-5/16” tall, and is centered 17-1/4” from the right end. I chose that distance so that the foot of the leg sits just to the left of the small bump on the cast iron platform. This might help keep the leg from collapsing if it were to be struck from the side?

The locking levers are 3-3/16” long, by 1/2” wide, and their pivots are 7/8” from the end.

Oh – and the note in the drawing about the upper/rear leg of the table being shorter is ambiguous. The front leg is 12-1/2”. The rear leg is only 12-7/16”. Don’t know why – but my 29-4 doesn’t seem to be symmetric there.

c.1969 Singer Fashion Mate Model 237

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written January 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

This portable Fashion Mate 237 (s/n ME167737) was purchased by my mother in 1969 or 1970, replacing the much older black Singer she owned before. (I wish I knew what model it was that she replaced! Piecing together memories, I think it was likely a model 66.) Her 237 came to me in 2003. The ME prefix on the serial number shows this was made in Monza, Italy – I believe all 237s were made there between 1968 and 1972.

The 237 was originally in a portable carrying case, which I discarded, sadly and stupidly, when I got the current cheap cabinet. Its potential future value didn’t occur to me at the time.

I don’t recall ever needing to repair the 237, in my youth, or recently.

I’ve been told that the 237 can be fitted to a treadle. That may be, but I think my mother would zig-zag in her grave if she learned that I’d removed a perfectly good electric motor in order to turn the machine into something her mother might have used! Edit: I have, since, tried the 237 on my MUTT treadle. It worked great!

| updated April 2021 | [index] |

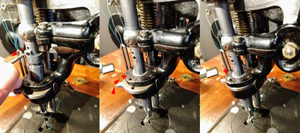

I got this machine out the other day to look it over, and make sure all was copacetic, and to my surprise, it wasn’t. It sewed fine, but the automatic tension release, when you lift the presser foot, wasn’t releasing. (Releasing the tension on the thread allows you to easily pull thread all the way from the spool and through the needle.) Now, most of my old machines don’t have a tension release at all, let alone automatic, so that shouldn’t be a big deal. But, in fact, to me, it is – if it’s broken, it needs to be fixed.

It turns out that while this is reputed to be one of the last “all steel” construction machines (referring to the insides, of course, obviously not to the outer skin!), it turns out that’s not quite true. There’s a very plastic part in the tension mechanism that should have been designed stronger than it is.

The center bar across that hole takes a bunch of spring pressure when the tension release is engaged, and wouldn’t you know, that little plastic “bridge” broke. After only 50 years. (Earlier models with a similar tension mechanism all use steel for that piece, btw.)

Clearly, if it wasn’t steel before, it should be now. So this was the repair. I wonder if it will last 50 years?

| updated October 2023 | [index] |

Someone in one of the sewing machine communities that I frequent expressed how much they wanted a nice example of a 237, for sentimental reasons, because it’s the machine their mother had used. Sound familiar? :-)

As it happens, I’ve been thinking for a while that I should rehome my 237. I’m not using it, in the way that it should be (after all, it’s only a little over 50 years old!), and I’ve been thinking it should go to someone who will appreciate it properly. So I got in touch, and the machine is now theirs. I’m thrilled to have found a new good home for it.

c.1900 Standard Rotary

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written long after the fact, in August 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I recently remembered that I almost started collecting truly “old” machines many years ago (2011), but for some reason either I didn’t have the time, or the machine that I happened on didn’t quite press the right buttons, or who knows what?

Anyway, the story was that friends of mine had picked a lovely Standard Rotary off the curb, with an eye toward refurbishing it. I believe they got as far as refinishing one drawer front before losing interest. So they gave it all to me. I was fascinated, but in the end, after cleaning it up just a bit, decided against keeping it. I gave it away on a local town mailing list, to someone who was clearly going to take good care of it. (The next machine I got, my 201-2, came from that very same list, six years later. :-) I probably only owned the Standard Rotary for a month or two.

From the looks of it, and from what I’ve now learned about the machine, and the Standard Sewing Machine Co., it was probably made in the late 19th century – the serial number (57930) is relatively low. The company was one of many that started up after the early machine patents all expired, making sewing machines much cheaper to build.

I love the lack of any cabinetry below the top. The wooden drawers ride on a delicate framework of cast iron.

1941 Singer Model 201-2

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written January 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I don’t know much about this machine (s/n AF787058). I received it as a “giveaway” from a member of a local town email list in early November of 2017:

“Hi, for you tinkerers out there I have a beautiful singer 201 that possibly needs a new motor. Would love to have it go to a good home rather than scrapping. It starts out sewing fantastically and then slows to a crawl. Have oiled and greased it but don’t have the energy to go further.”

The donor also said they “bought it at a yard sale down the street a few years ago”.

The cast-iron 201 was built (with various configurations of motor and other details) between 1935 and 1954. (A different looking aluminum machine took over the model number from then until 1962.) This machine is from roughly 1941.

The finish isn’t perfect – there are some chips in the japanning, and the shellac is crazed in some large areas. I haven’t yet detected a problem with the motor. The machine is gorgeous to hear – really. There’s no belt, because the motor drives directly through a worm gear drive, and the overall tone while running is just… different… than a belt drive machine.

Repairs: As part of a thorough cleaning and oiling, I replaced the motor grease wicks with new, and replaced all the grease with Vaseline petroleum jelly. Sadly I broke one of the wick’s spring clips while removing it, and fashioned a crude repair to make it work.

| updated October 2019 | [index] |

The 201-2 is a truly fantastic sewing machine. It sews beautifully, starts smoothly and slowly, and has a lovely sound to it. Some say it’s the finest machine Singer made, and this was an excellent example of the model. I sold it about 6 months ago because I really had no space for it, and I regretted it almost immediately, But I really did need to sell something – I had started having to stack machines on top of one another. I hadn’t used the 201 in a while, and it “didn’t fit my collection”, so it got the axe. But it turned out that the guy that bought it was essentially running a chop shop – he didn’t even want the cabinet, and was going to toss it, and ship the head overseas somewhere. Sigh – I didn’t think it was going to literally get the axe.

So, I’ve since gotten another one (also free), and while it sews well, it’s a bit of an ugly duckling compared to this one that I let get away. We’ll see how much I use it. If a lot, I’ll get a nicer one. If never, I’ll let it go too…

1916 Singer Model 66-1 Treadle

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written January 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I was given this Singer Model 66 (s/n G4620412) by my friend Scott in late November of 2017. Here’s what he wrote about it:

“The Model 66 was purchased by my grandfather, Joseph N. Merchant for his bride, Gladys H. Merchant (née Shufelt) in 1918 as a wedding present. They lived in Worcester MA for ~30 years, he was an engineer on the Boston and Worcester RR, she was a homemaker. They moved to Allston in the early ’50s and she worked at Raytheon in Allston before retiring. She sewed curtains, dresses, pants, as a regular event. They moved to Framingham in the early 60s and she continued using the machine as needed or requested. My grandfather passed away in the late 70s and she stayed in her house until her last year, 1988. The machine was always covered with a fitted cloth cover she made for it.”

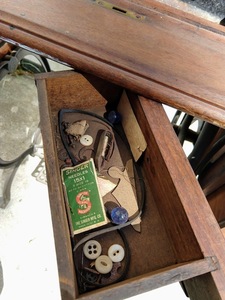

The machine was remarkably complete: all of the original attachments were still in the drawers, and all of the broken cabinet trim had been saved.

The Singer model 66 was made in various forms from 1902 to 1956. This treadle model was built, decorated with a couple of different decal patterns, from 1902 to 1923. This particular machine is from roughly 1916.

I “restored” the machine, which had gotten very old looking, and which was no longer operational. The whole process took about two weeks, working a few hours a day.

The head itself was extremely dirty, and while it could be turned by

hand, it was extremely difficult – enough that there was a worry of

breakage. The machine was cleaned with sewing machine oil, partially

dismantled, parts freed up, lubricated, and finally waxed (pure

carnauba) and oiled again. Some damage to the decals occurred, mainly

in the areas that were originally dark green. Most of the dark green

was already missing, but there were more gaps after I was finished

than before.

The head itself was extremely dirty, and while it could be turned by

hand, it was extremely difficult – enough that there was a worry of

breakage. The machine was cleaned with sewing machine oil, partially

dismantled, parts freed up, lubricated, and finally waxed (pure

carnauba) and oiled again. Some damage to the decals occurred, mainly

in the areas that were originally dark green. Most of the dark green

was already missing, but there were more gaps after I was finished

than before.

The cabinet had become stained and discolored, and the finish somewhat

crazed.

The top “working” surfaces were in relatively good shape,

structurally, though there was some delamination of the veneer on a

few of the edges. The drawers themselves were in good shape. (One

had been previously repaired, since it clearly has a replacement

knob.) The drawer cabinets were in bad shape: the veneer on all of

the large surfaces had begun separating, and splitting, anywhere from

3” to 8” from the bottom of the chest. Many of the add-on trim pieces

had already fallen off, but had been (thankfully!) saved.

The top “working” surfaces were in relatively good shape,

structurally, though there was some delamination of the veneer on a

few of the edges. The drawers themselves were in good shape. (One

had been previously repaired, since it clearly has a replacement

knob.) The drawer cabinets were in bad shape: the veneer on all of

the large surfaces had begun separating, and splitting, anywhere from

3” to 8” from the bottom of the chest. Many of the add-on trim pieces

had already fallen off, but had been (thankfully!) saved.

I completely disassembled the cabinet, anywhere there were screws to allow it. This made cleaning/repairing much easier. This picture was taken just before I began reassembly:

The veneer on the drawer sides was all reattached using Elmer’s

woodworker glue and lots of clamps. It was repaired without

further separating it, using a hacksaw blade to spread the glue into

the narrow space made accessible by gentle lifting of the veneer.

Loose trim pieces were completely removed, and then all the trim was

reattached, again using the same glue, and cushioned by padded blocks

when clamping.

The finish on all the wood surfaces was refreshed with Howard’s “Restor-a-Finish” (mahogany color), applied using steel wool. The product is a combination of strong cleaner and furniture stain, with solvents strong enough to soften old finishes. The steel wool helps with the cleaning process, of course, and also smoothes off rough edges of any imperfections (scratches, gouges) in the finish. After the Restor-a-Finish treatment, the cabinet pieces were oiled with Watco’s “Rejuvenating Oil”.

The treadle irons were cleaned with rags and sewing machine oil. A few pieces that were originally chromed (or nickeled?) were cleaned up with steel wool to remove rust. A few small brackets had lost all of their plating, and had rusted. These were cleaned and sprayed with lacquer.

I’m so pleased with how it all came out, that I have to include just a couple more “before” pictures, for comparison:

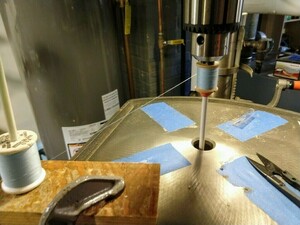

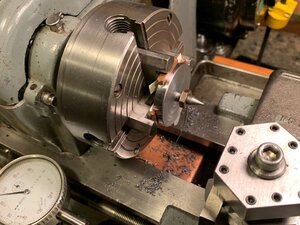

The only parts missing from the machine or cabinet were two small

pins, which are designed to keep the top drawer of the cabinet from

pulling out too far. The pins fit in two small holes in extensions of

the drawer sides, and their lower ends drop into milled channels in

the cabinet after the drawer is inserted. After seeing a picture of

the pins in a vintage parts list, I was able to make new pins from

a pair of common nails, using my drill press as an ersatz lathe.

| updated October 2020 | [index] |

Well, a few years have passed since I got this lovely model 66 and cleaned it up. I’ve been running out of space, and was thinking I probably needed to sell it or give it away. So I got back in touch with my friend whose grandmother it belonged to – I wanted to be sure he had the chance to take it back, though he had made it pretty clear in the past that he didn’t want it. Well, to my delight, he was more than happy to have it again! I’m really pleased a) that I got to have the fun of restoring it, and “owning” it for a while, and b) that it’s going back to it’s rightful owner. Perfect!

c.1968 Singer Featherweight “White” Model 221K

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written January 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

This cute little Singer Featherweight 221 White sewing machine (s/n F 198055, and more specifically, a model 221K7) was owned by Julia’s grandmother, Julia Spain Banta. It came to us in late December 2017, via Julia’s parents who also used it for many years. When they learned recently that I had a small sewing machine collection, they gave it into our care. The machine is in very good shape. The case, too, is in good condition, with just a few scuff marks.

These machines are called the “White” Featherweights, but Singer seems

to have referred to them as “Pale Turquoise”. In practice, people

thought of them as white, or mint green. It’s hard to capture the

color in a photo, but putting a white sheet of paper in the shot helps.

The “white” K7 machines were only made between 1968 and 1971 at the Kilbowie factory in Clydebank, Scotland. (The black predecessor machines, with some differences in design, were built in various places starting in 1933.)

The serial number is a bit of a mystery: “F 198055”, with a clear space between the ‘F’ and the digits. If that number was truly just “F198055”, then it would refer to a model 15K machine, made in 1920. In addition, these models are supposed to have serial numbers starting with “FA” or “FB”.

My pet theory (without any concrete basis) is that the second character on

the serial number stamping machine at the factory failed, and that

this sewing machine is actually an FA or FB machine. This is partly

reinforced by something I found, where someone had reported a

machine “with a SN of F (then a verrry faint ‘A’) 131629”. If the ‘A’

punch was already failing when their machine was made, it might have

failed completely by the time mine was made. By the time the

mistake was discovered, it may have been way too late to fix, on way

too many machines. There are other mentions of this class of

machines with seemingly out of place numbers as well, though I don’t

know whether they all start with ‘F’.

My pet theory (without any concrete basis) is that the second character on

the serial number stamping machine at the factory failed, and that

this sewing machine is actually an FA or FB machine. This is partly

reinforced by something I found, where someone had reported a

machine “with a SN of F (then a verrry faint ‘A’) 131629”. If the ‘A’

punch was already failing when their machine was made, it might have

failed completely by the time mine was made. By the time the

mistake was discovered, it may have been way too late to fix, on way

too many machines. There are other mentions of this class of

machines with seemingly out of place numbers as well, though I don’t

know whether they all start with ‘F’.

Repairs:

-

The gold-colored “badge” was missing. On this model, unlike most “badged” Singers, the badge isn’t a riveted piece of stamped brass – it’s just a foil sticker. Happily, reproductions are available, so that was an easy fix.

-

The masonite bottom plate, which acts as a drip-tray for the somewhat oily underside of the machine, was missing. I fabricated a new one based on a picture of the original piece, using measurements from the machine.

-

The clamshell speed controller was acting as a simple on/off switch – there was no variable control. I opened up the controller, and found that it has an adjusting screw which allowed the copper blade to press on the end of the carbon resistor as it should. In addition, electric arcing had perforated one of the brass switch contacts. I reinforced this piece by soldering on a strip of copper foil.

-

The lacquer on the machine appears to have been retouched at some point in the past. The touchups are obvious now, but perhaps the paint matched better originally. I have no idea where or when this retouching might have been done.

In May of 2018 we were given Julia’s grandmother’s first Featherweight, a black model from 1947. They make a nice pair.

| updated October 2020 | [index] |

I decided that while having two Featherweights was kind of fun, they didn’t really fit the older focus of my collection. So it seemed like one should go, and it was the newer of the two that didn’t make the cut.

1921 Willcox & Gibbs Automatic Silent Sewing Machine

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written late January 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

This is the first machine I’ve bought specifically to add to my collection. Willcox and Gibbs made and sold this machine, with a few variations, from 1858 through at least the 1930s.

Obviously it has a curious shape (from the back it looks like the letter G – the story is that this is related to the inventor’s surname), but in addition it sews a single-thread chain stitch rather the more common two-thread lockstitch. (Which is to say, it has no bobbin.)

I just got it recently (late January, 2018) today, so I don’t yet know all that much about it. It has serial number A666108, which means it was made 1921.

The price was right because a few things are wrong with it. Some I knew before buying (ebay), others I discovered after it arrived.

First, the spool arm is broken (and missing), and the connecting link

arm for stitch length control is broken (but all there).

I knew about both of these when I bought the machine, so they’re okay.

I think I can jury-rig a spool arm of some sort, and I may be able to

repair the link, but in the meantime the stitch length is still

adjustable from underneath – it’s just not convenient.

I knew about both of these when I bought the machine, so they’re okay.

I think I can jury-rig a spool arm of some sort, and I may be able to

repair the link, but in the meantime the stitch length is still

adjustable from underneath – it’s just not convenient.

In addition, the stitch plate, i.e., the

platform on which the cloth rests while sewing, has been replaced.

I should have seen this in the pictures before buying – somehow it never

occurred to me that the piece wasn’t original. However, every picture

of these machines that I’ve found shows a stamped

rectangular plate, probably nickel plated, and engraved with a

stitch/cloth/needle table, along with other labeling, like this one:

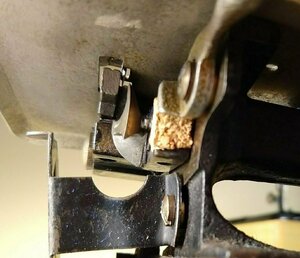

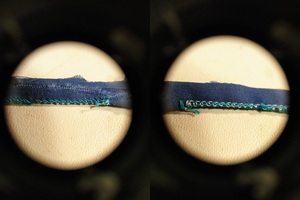

My machine, however, has a relatively crude unplated, unpolished steel plate. Milling marks are visible on the underside. There’s no engraving, and I believe it’s smaller than the usual plate. Despite the milling on the underside, this plate is much thicker than it should be, which prevents the feed dogs from ever protruding through their slot. The first picture shows the dogs in their fully raised position.

But the real problem with this stitch plate is the opening for the feed dogs.

Normally, with the presser foot down, resting on the dogs, the dogs will

break contact with the material being sewn as the retract through the plate

in order to move to the rear of the machine before coming up for another

shove. But with this plate, with its gigantic hole, the presser foot

simply descends along with the feed dogs, never losing contact. Useless.

But the real problem with this stitch plate is the opening for the feed dogs.

Normally, with the presser foot down, resting on the dogs, the dogs will

break contact with the material being sewn as the retract through the plate

in order to move to the rear of the machine before coming up for another

shove. But with this plate, with its gigantic hole, the presser foot

simply descends along with the feed dogs, never losing contact. Useless.

And finally: the axle on which the hand wheel turns is bent. Not much, but noticeably – it wobbles a few degrees when turned. It will certainly vibrate if it spins, so that will keep speeds down.

So it’s pretty clear that this machine was dropped – parts are broken, the stitch plate may have been bent and replaced, poorly, and the hand wheel axle is bent. But it’s also clear that it’s been well used, and the damage all seems old, making me think it can probably sew again someday despite its injuries. We’ll see.

| updated December 2019 | [index] |

After hoping I’d find a replacement cloth plate for the better part of two years, I decided it was time to get it out of house so it wouldn’t annoy me anymore. :-) Besides, I have four other W&G machines now, so while this was my first, and had some nice aspects, it was kind of redundant. It went to someone who just wants a shelf decoration. Perfect.

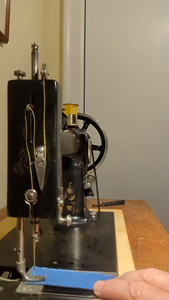

1914 Willcox & Gibbs Automatic Silent Sewing Machine

| written February 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

Yes, this is W&G machine number 2.

Soon after getting my first W & G chain stitcher (above), and realizing that it has some “issues”, another one (A592642) came up for sale nearby on craigslist. Not only did this one not have any of same problems my first machine had, but it came with case, motor, foot controller, and a slew of accessories and needles. (Never mind that just the day before I’d ordered new needles from ebay! :-)

The decals aren’t in as good shape as the first machine’s, but I was

sort of thinking it might be a parts donor for the first, and that

between them I’d end up with at least one excellent machine.

| updated December 2018 | [index] |

After buying my 1937 electric cabinet W&G machine, I didn’t really have a reason to keep this motor and base in my collection. I had repaired and rewired it, and I was able to sell it to someone who needed it. So all that’s left from this purchase is the 1914 machine itself, and the accessories that came with it.

After selling the electric base this machine came with, I moved it onto my hand-crank base. The lead picture on this blog entry shows it in that form. It now sports a replacement crank handle – which really is for a Singer Model 20. It’s small, but it will do, for now.

| updated late October 2023 | [index] |

I finally got the time, the materials, the weather, and the skills all in one place in order to make a new hand crank handle for this machine. I’ve hated using the Singer 20 toy machine handle ever since I got it, but it’s the only screw I’ve ever found to match the threads in the W&G wheel. So I’m still using that screw – it’s just counter sunk way into the end of the new handle.

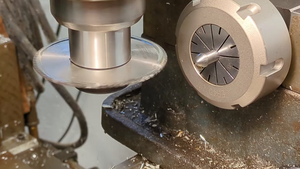

The new handle is walnut, and shellacked, as it should be. I’ve included

a few pictures of the making process, as well. (I actually got two

handles out of that piece of wood. The first one, in the “making”

pictures, didn’t work out due to a mistake, so I turned a second one.

No pictures of that happening – it was getting dark, and I was

hurrying. But that’s what you see installed on the machine.)

The new handle is walnut, and shellacked, as it should be. I’ve included

a few pictures of the making process, as well. (I actually got two

handles out of that piece of wood. The first one, in the “making”

pictures, didn’t work out due to a mistake, so I turned a second one.

No pictures of that happening – it was getting dark, and I was

hurrying. But that’s what you see installed on the machine.)

| updated March 2024 | [index] |

I’ve finally been able to replace that Singer Model 20 screw with a proper screw that matches the original that would have come on the W&G hand crank base. It’s one of the new screws that I turned myself on a metal lathe. Of course, now that I have the right length screw, I’ll need to turn yet another wooden handle, since the hole through the middle of the handle pictured above is the wrong size for the new screw.

Swapping parts between my Willcox & Gibbs machines

| added February 2018 | [index] |

Alas, it seems that not all W&G chain stitchers are created equal. I had been hoping to swap some parts from this machine to my first: the first machine has a homemade stitch plate, is missing the thread spool pin and arm, has a bent main shaft, and much of the nickel plating on the hand wheel is worn off. But in the end, only the spool pin and arm are compatible:

-

The W&G hand wheel has two cam surfaces milled onto it – one to drive the needle arm, and the other to drive the tension mechanism. The holes in the two machines’ tension arms are of different diameters, by just a couple thousandths of an inch, and the tolerance is so close that the hand wheels can’t be swapped.

-

The main shafts are different. There’s an small cam milled onto the looper end of both shafts, which drives the feed dogs. On the second machine the profile of that cam is entirely within the outline of the diameter of the shaft. On the first machine, the cam is larger, and “hangs over” the shaft diameter. So they’re incompatible. In addition, because of the larger cam, that shaft can only slide out to the left (hand wheel removed). But that shaft is bent at the hand wheel end, so it can’t come out at all – that shaft will never leave the machine.

-

Finally, I was really hoping to move the pretty stitch plate to the prettier of the two machines, to replace the homemade chunk of steel it came with. But that won’t swap because the feed dog mechanisms on the two machines are quite different. The head of one of the two little screws that hold in the round needle plate (where the feed dogs come through) interferes with the first machine’s feed dog movement.

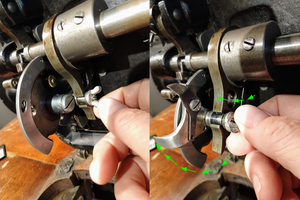

Willcox & Gibbs rotating hook

Perhaps the slickest part of the W&G machines is James Gibbs’ rotating

hook, which forms the chainstitch with just one moving part (in addition

to the needle). The hook manages to grab the thread loop that the needle

brings down, and holds onto it long enough and in such a way that the

needle will pass through that loop on its next stitch, at which point the

hook again grabs the needle’s (new) thread loop and the cycle repeats.

A video is worth a lot of words. (The camera angle changes, for the

better, I think, about halfway through.)

Willcox & Gibbs foot controller repair

| added February 2018 | [index] |

The foot controller for my second chain stitcher was completely dead. I’d found a good write-up on repairing them, but sadly, that controller was very different on the insides than mine.

My controller consists (essentially) of two coil resistors and a large flexible copper plate. The copper plate makes contact with successive points on the large resistor elements, as the pedal is depressed.

The resistors consist of a ceramic tube, wound with very thin wire. That thin wire isn’t what the copper plate makes contact with – it wouldn’t be strong enough, and any arcing would burn through it. To provide appropriate contact points, the tubes (and the thin wire winding) are each circled with 8 pieces of thicker copper wire, spaced along the length. These are just loops, with the ends tightly twisted together. These “wraps” are strong enough to act as an electrical contact with the copper plate, and are tightly held against the thin resistor wire. The whole tube was coated in a gray paste or paint which has dried and flaked off. My guess is that this was meant to keep the corrosion at bay.

Sadly, the copper wire “wraps” on my ceramic tubes were no longer electrically connected to the thin resistor wire underneath, due the obvious corrosion. I could put an ohmmeter on any area of the resistor wire, and get connectivity to the broad copper bands at the ends of the tubes, but there was no connectivity at all to any of the copper wire “wraps”. (The total resistance of each tube, BTW, is about 100 ohms, and the resistance between adjacent copper contact points is roughly 10 ohms..)

In the end, I carefully untwisted, removed, cleaned, and reinstalled all 16 of the copper wire wraps, and also cleaned the layers of fine wire underneath while it was exposed. Doing this restored all the right connectivity. Good as new!

Willcox & Gibbs Needles

| added May 2018 | [index] |

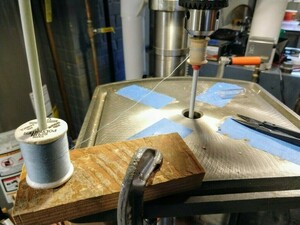

My 1914 machine came with a lot of needles. Thirty-two no.2 needles, ten no.4 needles, etc. Even one no.3-1/2 needle. Curious about their relative sizes, and prompted by some discussion on a Facebook W&G group, I took some measurements and a picture. First, shaft diameters:

| ID | diameter |

|---|---|

| #0 | .025” |

| #1 | .028” |

| #2 | .030” |

| #3 | .035” |

| #3-1/2 | .040” |

| #4 | .041” |

| GB90 | .036” |

(GB90 is a Groz-Beckert size 90)

Then a picture. I drilled a series of 5/64” holes in a piece of wood, and inserted a needle in each. These are just the W&G needles, sizes 4, 3-1/2, 3, 2, 1, and 0. Sadly, I forgot I had the Groz-Beckert needles until after I’d already drilled the holes and taken the picture. You’ll have to trust me that the hole in the G-B needle is even longer than that of the no.4 – it would definitely be the easiest to thread of the bunch, but its diameter is more like a no.3.

And here’s a picture of the Groz-Beckert packaging for the GB90 needles.

(Click to enlarge, as always.)

W&G Needles for heavy sewing

| added June 2022, based on an earlier email to the W&G list on groups.io | [index] |

I don’t do a lot of sewing, so having four W&G machines (plus a whole lot of others) isn’t really because I sew with them all.

But one that does get used is the W&G hand crank (American style, with the gears), which, with the crank handle removed, will fit in one of the bins that support the couch in our camper van. It’s the only (non-toy) machine I have that will fit that space, and it fits even when in a protective case, so it’s my on-vacation machine.

The trouble is, much of what I sew on vacation is repairs and mods, and the work often involves multiple layers, and nylon or polyester webbing. Backpack repairs, etc.

And until just recently, the W&G was just terrible at that stuff. I was always getting big loops on the bottom, which I’d assumed was due to the tension being off because of the thickness.

But I did some more testing recently, and discovered that the machine was perfectly happy sewing through other materials (leather, heavy material) that were just as thick.

So I did a bunch of experiments, with different materials, and different threads, and asked some advice over at the Victorian Sweatshop forum, and discovered a couple of things. Things that someone who actually sews very much would have known/tried a long time ago. :-)

First, one of the threads I had in the travel sewing kit was Coats & Clark “Button & Craft” thread. It turns out that not only is this the thickest (Tex 110, I think) thread that C&C sells (at Joann’s, anyway!), but it’s starched. Who knew? So it’s sticky. And it’s not really meant to be used in a machine. I’d picked it up long ago because it looked heavy duty – I just didn’t know any better. So I tried some others, and found that their “Outdoor”, and Dual Duty “Heavy” threads worked much better in my machine, but still not perfect.

And then I made the real “leap” – I got bigger needles! Doh! Again, should have done that a long time ago. I was using Groz-Beckert size 14 needles. I bought some of size 18, and… perfect. Everything I was having trouble with is just fine now, with perfect stitches even through several layers of nylon webbing. Even the Button & Craft thread is a lot better. (But not perfect, so I still won’t use it.)

I found the W&G size 18 needles at The Thread Exchange. There are links on that page for the #14, #16, and #19 needles. The #14 are the ones most often seen for sale on ebay, etc. If you need more details on one of their needles, you can get that from Groz-Beckert directly.

Willcox & Gibbs Tensioner Maintenance

| added February 2019 | [index] |

This 1914 machine has always had trouble sewing at the shortest stitch lengths. It hasn’t bothered me much, because I really have no need to ever sew anything at higher than 12 to 15 stitches per inch, and the machine sews fine in that range.

But it’s been on my mind to investigate, especially after another machine (my 1937, acquired later) had the same problem. So I did investigate, and did solve the problem – it was a simple matter of adjustment.

I’ve documented that adjustment, as well as how to do a full disassembly and reassembly of the tensioner, on my “Working on a Willcox and Gibbs Automatic Tensioner” page

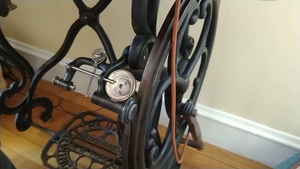

Willcox & Gibbs Hand Crank Reversing Brake

| added May 2023 | [index] |

I only just realized that while this machine has become one of my favorites, and I even carry it in our camper van when we go on vacation (just in case – I don’t use it that often!), I haven’t written anything about it in a long time.

And it turns out there is something I haven’t mentioned. The American-style hand crank bases (so-called, because they were American-made, and quite different than the British-made belt-driven hand crank bases) have an ingenious little feature.

The W&G treadle bases all have a “brake ball”, which is a small rubber

ball that bounces along in a cage alongside the big treadle wheel,

until you try and treadle backwards, at which point it jams up solid,

preventing you from turning the machine in the wrong direction. Well,

it turns out these hand crank bases have the same feature. There’s a

small hole through the pillar which will accept a thin piece of

leather cord. I’ve used a piece of treadle belt, but I had to taper

it to get it to fit – presumably thinner cord would have been used

originally. A small set screw holds it in place.

The cord is positioned so that it bounces along on the large gear’s teeth while you crank the machine, but when you try and turn the handle backwards, the leather is dragged into the interlocking teeth, and the crank is immobilized. Clever!

1871 Singer “New Family”

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written May 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I had told myself, since our house is out of convenient corners with extra floor space, that I shouldn’t collect any more treadle or cabinet machines. But when I happened to see this machine on Facebook Marketplace, I had to go take a look.

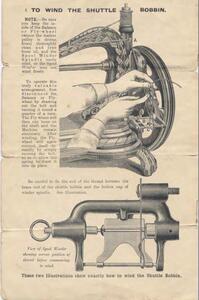

It seemed pretty undervalued (even with my rudimentary knowledge), and sure enough, it turned out to be a “New Family” machine, with mother of pearl inlay. The entire line of machines of which this is a part ran from 1863 to 1902. These were the first mass-market mass-produced sewing machines made. This “New Family” model was made from 1865 to 1877. Before that (for just a couple of years) was the “Improved Letter A”, and after 1877 (25 years) came the “Model 12”. All three variants are quite similar, obviously with improvements and changes along the way. Mine (s/n 618146) was made in 1871.

One nice feature of these machines is the type of shuttle

mechanism they use, called a “transverse shuttle”. If one thinks of a

lockstitch sewing machine as being a sort of one-threaded loom, then

this is about as close as one can get to that mental model. The

shuttle is boat-shaped, with a pointy end, much like a loom’s shuttle.

Also like a loom’s shuttle, it carries a narrow cylindrical spool of

thread (the bobbin). It moves linearly back and forth beneath the

presser foot: the needle comes down, and retracts somewhat to leave a

small loop of thread. The shuttle passes through the loop from left

to right, and the needle retracts the rest of the way, forming the

stitch. The shuttle then retreats to the left, and is ready for the

next stitch.

Also like a loom’s shuttle, it carries a narrow cylindrical spool of

thread (the bobbin). It moves linearly back and forth beneath the

presser foot: the needle comes down, and retracts somewhat to leave a

small loop of thread. The shuttle passes through the loop from left

to right, and the needle retracts the rest of the way, forming the

stitch. The shuttle then retreats to the left, and is ready for the

next stitch.

My machine’s cabinet is in very good shape. That’s likely

helped by it being made from solid boards – no veneer. The “coffin”

looks like a simple box cover, but actually unfolds in a very clever

way to make a large sewing surface.

The machine head is also in good shape for its age – the decals are

very worn, but the mother of pearl highlights are all present.

There’s very little rust, and the paint is mostly intact. It’s

currently missing the shuttle (which holds the bobbin), so it won’t

sew for the time being. The axle and wheel for the bobbin

winder is also missing, as was the tension adjusting screw, but I’ve

been able to get a replacement for that. Everything else seems to be

there.

The treadle irons are rusty near the floor, but should still clean up pretty well. The original ceramic (I think) casters are both intact. I love the free form design of the irons.

| updated October 2018 | [index] |

I was able to procure a Model 12 shuttle, and a matching bobbin winder assembly, from Helen Howes in the UK. With shipping, they cost about the same as the rest of the machine. All in the name of the hobby, I guess.

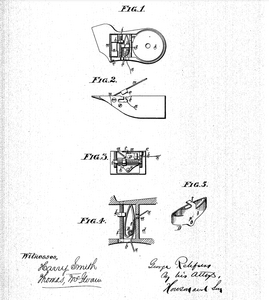

I had some trouble initially getting the machine to sew, but with lots of

advice from the folks on the Victorian Sweatshop forum, I got

it sorted out. It turns out the only real problem was with my replacement

shuttle. There’s a springy piece of steel that runs along the side of the

shuttle, which helps keep it aligned and in place during its travels to and

fro. The rivet which should hold that piece in place had become loose on

my shuttle, allowing the spring to catch on the underside of the feed dogs

midway through the shuttle’s forward stroke. I took a video of the

problem:

A punch and a small hammer took care of tightening the rivet, and all was well.

Sadly, due to the lovely fold-out design of the treadle top, I can’t display

the New Family on its treadle, since to open it up requires too much

floor space. So I made a simple display base, and it fits on top of a

bookshelf. Looks fine.

Sadly, due to the lovely fold-out design of the treadle top, I can’t display

the New Family on its treadle, since to open it up requires too much

floor space. So I made a simple display base, and it fits on top of a

bookshelf. Looks fine.

| updated February 2019 | [index] |

I’ve been thinking of selling this machine, since it’s so hard to display properly. As part of putting an advertisement page together, I took some photos of the folding top, and realized I’d never really shown that feature here. It’s pretty cool.

| updated October 2019 | [index] |

I couldn’t bring myself to sell it. :-) Here are a few more pictures, simply because it’s so pretty.

| updated April 2022 | [index] |

Well, I’ve made a couple of half-hearted attempts to sell this over the last few years, but nothing ever happened. But not being able to display it in the treadle (since it takes so much extra floor space when opened up) meant that it spent a lot of time in the cellar, which just didn’t seem right. So it’s a pretty little thing, but it’s now moved on.

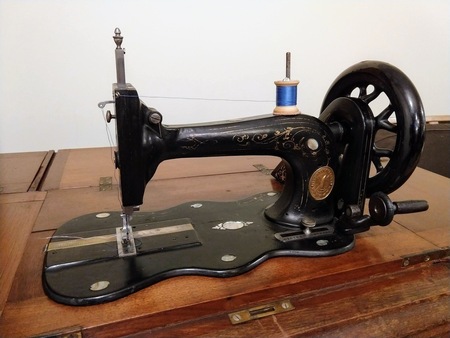

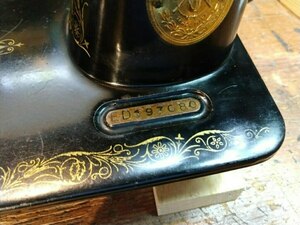

1941 Singer Model 99K Hand Crank

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written May 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I’ve wanted a hand crank machine for a while – partly just to try sewing on one, and partly because there are just three common ways to power a sewing machine, and I already have examples of the other two. The Singer Model 99 is closely related to the Model 66 that I have in treadle form – it’s basically identical, just shrunken a bit (1-1/2” lengthwise, 1/2” back to front), making it more portable. It was produced from 1911 to 1962 or ‘63. This one (ED197080) was made at the Scottish Kilbowie plant in 1941. The hand crank is original – there is no wear whatever on the hand wheel pulley, so it’s likely never been treadled or attached to a motor.

These pictures were taken after a fairly superficial cleaning – the paint was wiped down with sewing machine oil, and the prominent chrome pieces were rubbed with steel wool. The bobbin slide plate is missing, and I’m hoping to find a vintage replacement. Modern replacements are available, but they look like what they are: modern replacements.

Of course I’ll need to find, or build, a base of some sort to make the machine useable. But I can afford to do a little work on it.

Later… Okay: display case has been built, the bobbin and needle plates have been replaced, and spit and polish applied. Looks pretty good!

| updated November 2020 | [index] |

I’ve recently had an influx of hand cranks, meaning I have a space crunch. This one, which has long been a favorite, didn’t make the cut – it’s a little new for my collection, and a friend of mine was very interested in it. I’m glad it’s found a good new home!

1947 Singer Featherweight Model 221

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written May 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

A second Featherweight joined the family. Or, rather, it stays in the family, thanks to my generous in-laws. Like the white 221K Featherweight I already had, this 1947 black Featherweight (AH198050) also belonged to Julia’s grandmother. She must have liked it, given that she bought a second!

This one needed a little more restoration than the first – the electrical cords were worn through, the rubber foot pads had turned to goo (literally!), and there was a fair amount of dust and cat hair to clean up. But it’s a solid little machine under all that.

Warning! The 3-wire plug in this picture was

assembled incorrectly, and is very dangerous, even if the wiring itself

were in good shape. Two of little brass tubes will be “hot” if the

cord is plugged into the wall. When assembled correctly, those tubes

are reversed, and will not protrude.

Warning! The 3-wire plug in this picture was

assembled incorrectly, and is very dangerous, even if the wiring itself

were in good shape. Two of little brass tubes will be “hot” if the

cord is plugged into the wall. When assembled correctly, those tubes

are reversed, and will not protrude.

I wanted to rewire it with something that was at least a little bit

“vintage”. Regular modern zip-cord didn’t seem like it would look

right. I found a place that sells cloth-wrapped cord, and got some in

black. (They had both cotton and rayon – I chose rayon.) The

original cords had clearly failed due to lack of strain relief where

they entered the controller and plug, so I used layers of shrink wrap

to add protection there – perhaps too much.

The only piece that was truly damaged on this machine was the bobbin

winder. I’m not sure what happened to it, but the wheel that needs

to ride nicely on the drive belt, in order to spin the bobbin, had been

mangled: it was no longer flat, and it was no longer round. It’s

made of aluminum, so it bends easily, but still – how did that happen?!

The damage is easier to appreciate in a

short movie, which shows it well.

Happily, fixing it was a lot easier than I thought it would be. Singer only sold the assembly as a single part number – so it seemed like it might be impossible to work on the wheel by itself. But some helpful folks that specialize in Singer Featherweights told me the bobbin winder was pressed together. (They also sold me some new rubber feet to replace the old gooey ones.)

I was able to get the wheel off the axle just by tapping on the wheel

end of the axle with a small hammer.

After that, a squeeze or two in the vise flattened out the wheel, and I had

a couple of Craftsman sockets (both 19mm, from two different sets)

that were just the right diameters to gradually work out the

out-of-roundness. I forced each in turn into the cup of the wheel,

again using the vise, and also did a bit of hammering on the rim to

get out the remaining high points while it was still on the socket.

Finally, I pressed the axle back in, using a large nut as a spacer to keep

the wheel from getting squished while the axle went in:

The result is way better than I expected.

A second movie shows the (vast) improvement.

Okay, then, with all that out of the way, here are a couple of glamour shots of the machine, all finished up:

Finally, I don’t think you can own a pair of black and white Featherweights and not photograph them together:

| updated January 2025 | [index] |

I’ve long felt that this machine should really go to someone who could use its capability and portability to full potential. When an accomplished sewist from the Victorian Sweatshop forum lost her home in the recent LA fires, it made perfect sense to send to her. I hope it serves her well. (And, I hope it gets there in one piece! Shipping sewing machines is a risky business… :-/ )

c.1880 Wheeler and Wilson No.8

| written June 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

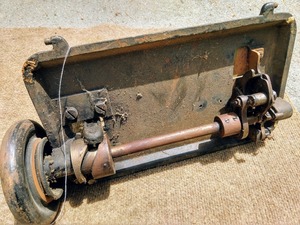

This 1880-ish Wheeler and Wilson model No.8 (s/n 265363) is complete, it turns over (sluggishly), the cabinet is in good shape, and it has quite a few accessories, including more glass presser foot inserts. Clearly it needs work, but I’m really pleased with it. Stay tuned!

Allen Wilson was a very clever guy. He held patents for the vibrating shuttle mechanism (which his machines didn’t use, but lots of others’ did), the round bobbin and rotary hook mechanism (which his machines did use, and which many still do today), and the up/forward/down/back four-motion feed (which is still universally used today). Oh – and there’s a nice write-up on the No.8 on the ISMACS site.

This machine also has a paired drive pulley setup, allowing it to be operated at two different drive ratios. You can see the two belt grooves in the closeup of the large treadle wheel, above. My Singer 29-4 is currently the only other “two speed” machine I own.

| ... continued, October 2018 | [index] |

Okay, I’ve finally done an initial cleaning and oiling of the machine’s head, cleaned up the treadle irons, and refinished all of the wooden parts. I’m very pleased with the result!

In addition to cleaning the case, I’ve also cleaned the head enough

to get it to sew. I have trouble imagining how sewing machines get

so dirty sometimes. I think in the case of the old ones, it’s the oil:

many would originally have used sperm oil (i.e., from sperm whales) rather

than a petroleum-based oil. When the whale oil dries, it leaves

horrible, hard, brown, caked-on crud. Yuck. These parts didn’t get

cleaned: it would have been hard, and the mess isn’t hurting anything.

It looks liquidy in the pictures, but it’s not: it’s like hard shellac.

Restoration note:

As with my Singer Model 66, I used Howard’s Restor-a-Finish on this. I haven’t yet seen any compelling reasons not to use it, and it’s practically “wipe-on/wipe-off”. The results are perfect, for my taste. “Patina” (that’s latin for nicks, scratches, and stains, right?) is preserved, while the piece becomes living room friendly. I might not use it on fine furniture, or on something where preserving or reproducing the original finish was crucial, but for a mass-produced sewing machine? Probably fine.

I do clean the wood first, quickly, with Windex glass cleaner and paper towels. And I apply the Restor-a-Finish with #0000 steel wool. Here are a few before/after shots:

Oh – the other product that makes this stuff easy is Evapo-Rust. Just soak a rust-encrusted part in it, and all the brown flaky crud disappears. As a bonus, it’s safe, non-toxic, and can be poured down the drain when it’s used up.

Here’s the bobbin winder, which is made of a different alloy than the cast iron treadle irons, so it had rusted badly. But it’s fine now, other than still needing a rubber tire, obviously.

1922 Singer Model 99K-13, electric

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written June 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I don’t need, or even particularly want this machine (Y702893). But the bent wood case is in pretty good shape, and my 99K hand crank doesn’t have a case at all. So I bought it (quite cheaply) for the case. As it happens, the machine is in reasonable shape, though it needs badly to be cleaned, oiled, and rewired. And the controller has some dead spots, and the controller knee lever is missing, (Okay, maybe my definition of “reasonable shape” is starting to skew a bit.) I’m not sure what I’ll do with it – now that I have it, of course, my “preservationist” side keeps saying “Restore it! Restore it!”, while my practical side says “Just fix the case so you have a complete hand crank model, which is all you ever wanted.” I wonder which side will win?

| updated November 2018 | [index] |

Well, in the end I couldn’t bring myself to part out the machine. So I gave it a new foot controller (the knee controller was burned out and unfixable, and the knee bar was missing in any case), shined it up, refinished the case, and sold it. It looked pretty good by the time I was done.

1926-1950 Singer Model 20 Toy Chain Stitcher

| written July 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I got this cute little chain stitcher from Julia’s brother-in-law for my birthday. The Singer toy machines don’t have serial numbers, but various features on this one show that it was made in the 25 years or so between 1926 and 1950. It has a little rust on the cloth plate, and the felt on the base could be replaced, but it looks and works fine otherwise.

It’s an excellent machine for demonstrating how single-thread

chain-stitchers work, since unlike my

Willcox and Gibbs machines, it’s

light enough to hold and operate in mid-air, and the underside offers

an unobstructed view of the hook.

It’s an excellent machine for demonstrating how single-thread

chain-stitchers work, since unlike my

Willcox and Gibbs machines, it’s

light enough to hold and operate in mid-air, and the underside offers

an unobstructed view of the hook.

Willcox & Gibbs Hand Crank, with 1904 parts machine

| written July 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I’ve been on the lookout for a hand crank for my W&G machines for a while,

so when this popped up on Craigslist, I grabbed it. It didn’t hurt that

it was dirt cheap (relatively speaking).

The machine (s/n B544060) is quite rough (note the JB Weld and wired-on sheet-metal repair!), and a large part of the lacquer is missing on the crank wheel, but the price was right. With a little oiling it started spinning over quite nicely. I haven’t tried sewing with it, but I suspect it will be fine

The only big issue is that the crank handle itself is missing, along with the screw that holds it. Of course the missing screw is 11/64”, and 40tpi. That’s the same threads as the W&G attachment thumbscrews, and, ironically, also the same as the crank handle screw on the Singer Model 20. Maybe I can share my Model 20’s handle between the two machines! In reality, I may end up drilling and tapping the wheel for a more modern screw size. [Edit: in the end, I got another Model 20 crank handle and screw from ebay, and I use that.]

In the end, I bought this machine not for the machine, but for the hand-crank base. The base now sits under my second W&G, since I sold the electric base that that machine arrived with.

| updated December 2018 | [index] |

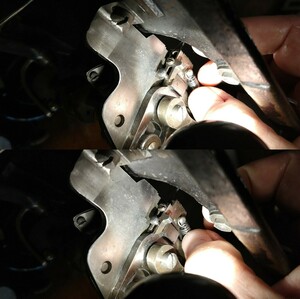

The hand-crank base’s feet were shot: mushed out, brittle,

and, while they would still protect a tabletop, they’d lost any stickiness

they’d ever had, so the machine wouldn’t stay put on a smooth surface while

sewing.

The feet are of the “rubber plug” type, which fit into holes milled in the base. The holes are just under 1/2” in diameter, and 1/2” deep.

It turns out McMaster-Carr carries the perfect replacement, as part number 9305K32. They’re in the “Push-In Bumpers with Compressible Stem” section. They fit perfectly, and have plenty of “stick”.

The second picture shows one new foot installed (on the right), and also

shows an old foot shaved off with a razor blade, before I pried the

rest out with a thin-but-strong screwdriver. If you have a situation

like this, and don’t have proper replacements, trimming the foot flat

leaves a nicer surface for a stick-on foot than prying out the old

rubber and leaving a hole.

| updated December 2018 | [index] |

While I still have the castings for the 1904 machine itself, most of its parts have been transferred to the 1893 machine that I got with my treadle base. The decals were good on that machine, and, let’s face it, that repair to the 1904’s needle arm lever wasn’t very attractive.

Custom Sewing Machine Display Bases

| written July 2018 | [index] [index by age] |

I’ve made several bases for machines now. I’ve used three different techniques. It’s been fun.

My Singer 99K hand-crank didn’t

come with any sort of base, or case. Because I might like to travel

with it someday, and room in our van is limited, I made the base as

small as possible. There isn’t yet any attachment of the machine to

the base – I’ll deal with that when it’s used for more than

displaying the machine on a bookshelf.

My Singer 99K hand-crank didn’t

come with any sort of base, or case. Because I might like to travel

with it someday, and room in our van is limited, I made the base as

small as possible. There isn’t yet any attachment of the machine to

the base – I’ll deal with that when it’s used for more than

displaying the machine on a bookshelf.

I used my Kregs jig to install pocket screws to hold it together, and carved the top to match protrusions from the base of the machine. It’s barely larger than the sewing machine’s base. The holes in the ends are for one’s fingers, when picking up the machine.

My mother’s Fashion Mate 237

originally came in portable plastic carrying

case. I was dumb, and got rid of that when I found a floor cabinet

for it. Now I don’t have room for the cabinet, so I again need a small

base to make the machine useful. This one actually uses hinges, just

like a “real” case. I did my first rabbet joints for this one. I also

included an extendable “kickstand”, which does two things: it keeps

the base from flipping up when the machine is leaned backward, and gives

the back of the machine something to rest on.

My Singer New Family came in a beautiful treadle stand, with a

flip-out cover that forms a large sewing surface. The trouble is that

when the machine is displayed in the open position, the effective

floor space taken by the treadle base and surface is huge. So I

needed a more compact way of putting my oldest machine on display.

My Singer New Family came in a beautiful treadle stand, with a

flip-out cover that forms a large sewing surface. The trouble is that

when the machine is displayed in the open position, the effective

floor space taken by the treadle base and surface is huge. So I

needed a more compact way of putting my oldest machine on display.

I repurposed an old butcher block top, which had the necessary depth. It was pretty easy to cut with a hand-held jigsaw. The outline for the cutout came directly from a tracing of the treadle top.

I used the same technique (and the same piece of old butcher block!) for my 1906 New Ideal as well.

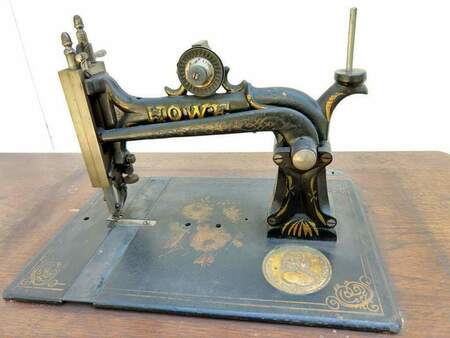

1871 Howe “Letter A”

(Gone! No longer mine.)

| written July 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

In 1846, Elias Howe patented the needle with the eye at the pointy end, and, in the same patent, the two-thread lockstitch still used by almost all domestic sewing machines today. He didn’t build machines right away, but his family did. When he finally started, in 1863 or so, he produced this machine, which is known as a “Stockwell Howe” to differentiate it from earlier Howe sewing machines made by another branch of his family. (He was in business with his two sons-in-law, who were brothers named Stockwell.)

This one sat on Facebook Marketplace for at least a month before I decided to look at it. It’s in very good shape – the seller said it came from his grandparents house. They must have taken good care of it. “Letter A” is simply The Howe Machine Company’s name for the model. The Letter B, C, and D machines were bigger and successively more industrial. The serial number (178732) dates it from 1871.

Note that unlike most other machines, there is no wheel above the table. To start the treadle, or move the needle, one must reach underneath and pull on the belt.

There are essentially three things which must move in synchrony on a sewing machine – the needle, the shuttle or bobbin, and the feed dogs. On this machine the L-shaped needle bar is driven by the right most groove in the large drum underneath. The groove to its left drives the shuttle forward and backward under the needle. The feed dogs are driven by a much smaller eccentric cam near the left end of the shaft. Stitch length is controlled by turning the knob at the left end, to adjust how much the cam moves the feed dogs.

I tried to get some of the gunk off the undercarriage, but only succeeded in cleaning enough to make everything move smoothly. I’m sure sperm oil is to blame.

Cleaning the upper parts was more successful, as was cleaning up the

base. This one qualifies for a prime living room location:

And after minimal setup, it sews!!

I made a short movie which shows the machine in action:

There’s no cloth or thread, in order to show how the shuttle

moves. I love that this was made in 1871.

There’s no cloth or thread, in order to show how the shuttle

moves. I love that this was made in 1871.

| updated September 2020 | [index] |

Sometime last year I was looking at the pictures, above, of the cruddy underside of this otherwise pretty machine, and decided to do something about it. I didn’t do a lot of disassembly, but was able to get almost all of the caked grime off of the big cam cylinder. It looks much better!

| updated May 2021 | [index] |

A note on needles. I can’t remember why I tried them, but I’ve found that needles from my Singer 29-4 work very well in the Howe. This is handy, because while the ISMACS needle cross-reference lists dimensions for the Howe needle, apparently there are no modern sources. The total length, and the length to top-of-eye, both closely match that of the readily available 29x3 (or 29x4, for leather work) needle very well, but the diameter should be smaller: 1.93mm vs. 1.98mm. The needles I own are all 1.95 or 1.96mm, and seem to work fine in my machine.

| updated January 2022 | [index] |

Someone mentioned that the serial number on a Howe is under the front slide

plate, which I didn’t think was true – mine is on the rear slide plate.

Well, I was happy to be wrong. Turns out the s/n is in both places.

Someone mentioned that the serial number on a Howe is under the front slide

plate, which I didn’t think was true – mine is on the rear slide plate.

Well, I was happy to be wrong. Turns out the s/n is in both places.

| updated April 2022 | [index] |

This machine was spending way too much time in the semi-finished cellar due to lack of display space upstairs. I actually do see it quite a bit, since I’m down there a lot, but still. I now have a few machines of similar style, so that, coupled with the lack of joy it brings me to sew with this one, meant it was time to go. (Something had to go – I currently have more machines than places to put them.)

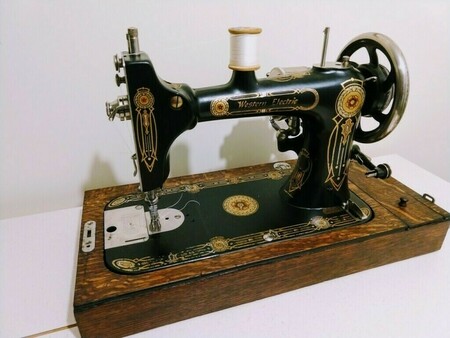

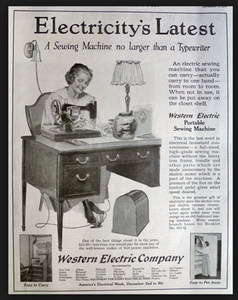

c.1918 Western Electric No.2 Portable

| written August 2018 ... | [index] [index by age] |

I couldn’t resist picking up this Western Electric machine (s/n A80864), which dates from 1917 or 1918. At least, those are the commonly internet-quoted dates of manufacture. I’ve not been able to find a hard reference. The machine was actually built by the National Sewing Machines company, and badged for W.E. It’s the same machine as the National Model ‘A’, or perhaps ‘A2’, introduced in 1910, and electrified for Western Electric in 1917. Perhaps Western Electric only badged it for two years.

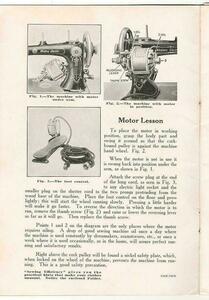

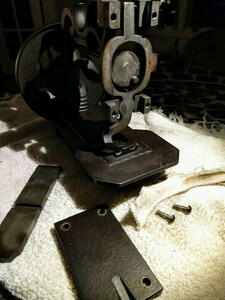

Partly I wanted it because the decals are pretty, and fairly well preserved – I don’t have many machines with pretty decals. Plus, I used to work for AT&T, which was Western’s parent company. But it also has this crazy motor arrangement, where the motor is mounted on swivels, and its position is controlled by a spring: it can either live tucked into the machine for storage, or swiveled to where it drives the hand wheel via a friction wheel when in use. I have two friction wheels – one is the original cork covered one (at least, according to the manual), and the other is a later rubber one.

Interestingly, about half of the old pins I found under the base couldn’t be picked up by a magnet – I believe they’re plated brass.

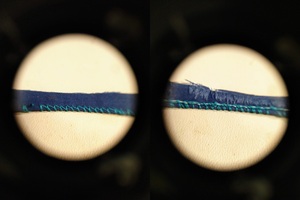

The bobbin winder is also unusual – it’s driven directly from the

motor by a coiled metal spring “belt”. When doing this, the friction

wheel is held off the hand wheel by deploying a small arm.

It will need some thorough cleaning, and likely the motor needs rewiring. There is no controller or plug – I’ll have to come up with something. Too bad I don’t have the original – it was pretty cool looking, and it came with a lightbulb-like screw on the end of the wire for getting power! I guess when electricity first became commonplace, it was just for lighting: there were really no appliances yet, so this made sense. See this advertisement, and also Figure 3. (Amusingly, the advertisement also shows an electric lamp on the table. Which must be plugged in somewhere. So why not plug the machine in there too?)

Sadly… after a thorough cleaning, and testing, and dismantling, and diagnosing… the motor is dead. There’s a break in one of the field windings, and the armature windings seem to be shorted together. So, it’s to be a shelf queen. Oh well!

But at least it did clean up nicely!

| updated December 2018 | [index] |

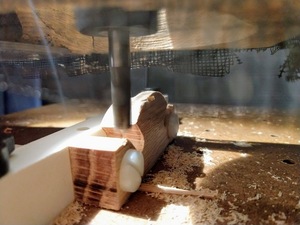

I found a motor! It was sold originally as a general purpose sewing machine motor – you could use it to convert your treadle machine to electric power by sitting this thing behind your machine, with the roller in contact with your hand wheel. The motor was spring mounted.